Maul and Excite — An interview with David Fincher

A version of this was originally published in The Scotsman in September 2008.

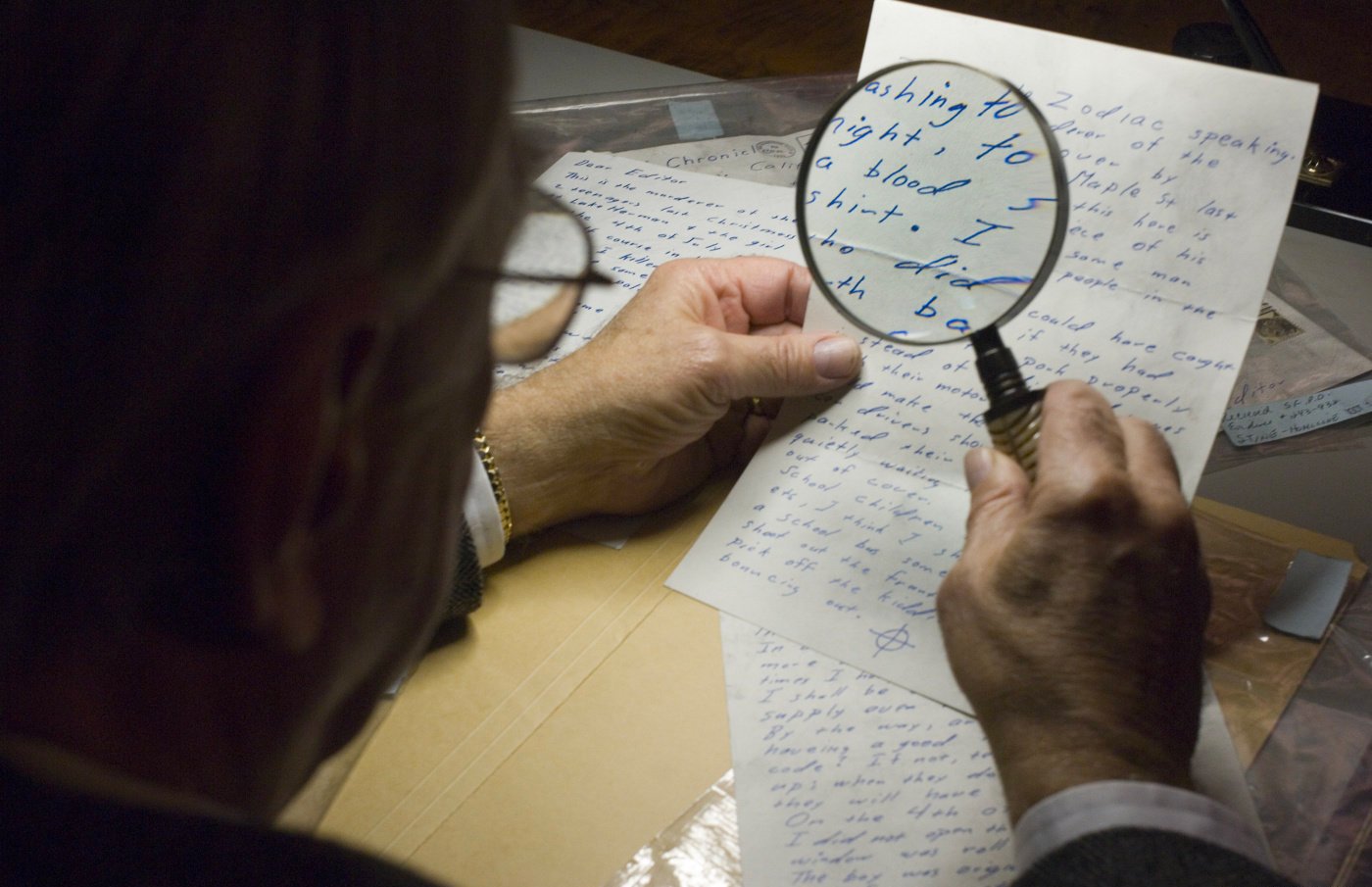

The biggest misconception people have about David Fincher is that he’s dark. No, scratch that. “That’s just the dullest,” sighs the director who served up Gwyneth Paltrow’s severed head in a box in Seven and plunged corporate America into financial chaos at the end of Fight Club. The other misconception, the one journalists tried to tag him with in the wake of last year’s critically adored, commercially ignored Zodiac, is that he’s obsessive. “I don’t agree with that, I think that’s too easy.”

Probably best not to brand him a tortured artist then, right? “Nope, I try not to be tortured. I don’t even know what that is; why do people always want you to be tortured? I feel lucky to be doing what I’m doing.”

How about Fight Club producer Art Linson’s description of him as “someone whose ambition is to maul and excite?”

“To maul and excite? Yeah, I like that. That’s probably the nicest thing he ever said about me.”

So it’s an accurate description? “I’m not exactly sure what it means, but I’ll take it.”

It’s a Monday afternoon in September and David Fincher is on the phone from Los Angeles. We’re supposed to be discussing the belated British DVD release of his director’s cut of Zodiac (“Isn’t that out already? It’s been out here since January”), but we’ve drifted into a record-straightening discussion about his reputation instead. Partly that’s because we’ve just been talking about his new movie, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, his third collaboration with Brad Pitt (after Seven and Fight Club), and a film that may well confound a lot of Fincher fans when it goes on release in America on Christmas Day.

But more on that later. Right now we’re discussing his public persona because, well, a lot of myths seem to have grown up about David Fincher in recent years. Put it down to the “cult of the director”: because he takes his time picking projects, because he’s meticulous about his work, because he’s been responsible for some of the most visually striking and provocative pieces of American cinema in the past 15 years, and especially because he considers it fiscally responsible to do a lot of takes (sometimes as many as 50 or 60) rather than risking the possibility of expensive re-shoots at a later date, there’s been a tendency to try and paint him as a Kubrick-style control freak.

It’s something the 45-year-old director puts down to ignorance of the filmmaking process. Doing lots of takes is not a luxury, he says, nor is it a sign of crazed genius, a myth he wishes would be dispelled, but probably won’t be any time soon. “I’m just hoping people get bored with it.”

To this end he seems keen to play down any notions of having an exalted status within the industry. He laughs off any suggestion that his name alone can secure him the actors he wants and any mocks the suggestion that any of his films, even Fight Club and Zodiac, come close to perfection. “Never got perfection,” he chuckles. “Looking forward to it.”

What’s more, his answers seem geared towards puncturing pomposity. He’s not one for anecdotes or effusive analysis of his work, preferring sarcastic quips and self-deprecating put-downs.

Try getting him to reflect on why he works so well with Brad Pitt, for instance, and without missing a beat he says, “We both like a lot of takes.” Mention that you recently re-watched all his films and he sounds genuinely aghast: “Good god, why?”

Ask if he has a theory about why Zodiac didn’t take at the box-office, and he expands on his initial “Nooooo” with the following: “I guess people just don’t like irresolution. But, you know, that’s what I thought was interesting about it. And I was wrong.”

Ask him about the critical furore over Fight Club, when he was accused of being a sadist, anti-God and, outrageously, of inciting fascism by “echoing propaganda that gave licence to the brutal activities of the SA and the SS” (see the late Alexander Walker’s review in The Evening Standard for that choice cut), and he just laughs. “As I like to say, you do the best you can do and then try to live it down.”

Such glibness can be a little frustrating for an interviewer, but it’s also funny, and probably healthier for Fincher than getting hung up on the way he’s repeatedly been pilloried then vindicated for the work he’s done over the years. He’s certainly a reluctant axe-grinder, especially considering the well-publicised baptism of fire he received while making his heavily compromised debut, Alien 3. What did that film teach him? “To take responsibility for every thing on a film.” It’s the reason he reckons the studios probably like working with him now; it absolves them of any blame should the film not succeed.

Of course it helps that audiences tend to come round to his films eventually. Zodiac’s star is already in the ascendent, with high profile endorsements from the likes of crime writer James Ellroy helping it filter into the mainstream. It may even follow the lead of box-office flop/DVD smash Fight Club. Fincher considers that film his most personal and was heartened recently when he walked into a hotel lobby and saw a group of twenty-somethings sitting around watching it on TV. “They were laughing their asses off and it was like, thank god someone’s finally getting this movie for what it’s supposed to be. I mean, we wanted to offend people a little bit, I won’t deny that, but it was hardly as incendiary as people made it out to be.”

The after-life of Fight Club has been astonishing, with Fincher quoted on more than one occasion that he’d like to see it turned into a musical to celebrate the film’s tenth anniversary next year. The First rule of Fight Club is you do not sing about Fight Club? Battling it out with Mamma Mia! and Hairspray for Broadway supremacy? Was he being serious?

“I was being serious, but it’s an expensive proposition and not a lot of people are lining up to take big risky propositions. But I would love to. I think it would be funny.”

It would certainly be a shock to the system, maybe even as much as the forthcoming The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Loosely based on a short story by F Scott Fitzgerald about a baby who is born old and ages backwards, Fincher is currently in the final few weeks of post-production, supervising the elaborate frame-by-frame special effects that have been necessary to digitally age Brad Pitt in reverse. “The film takes forever to explain, but it’s about life, that’s all I know,” says Fincher, who has been involved with it for the best part of seven years. “I like to think of it as being about the dents that we make on each other, that’s the best description I can think of. I think it’s really heartfelt.”

Heartfelt. That’s the thing that might throw Fincher fans, especially since it has been adapted by Forest Gump screenwriter Eric Roth, was once a project for both Steven Spielberg and Ron Howard, and is starting to be talked up as a potential Oscar candidate (Fincher insists the favourable Christmas US release has more to do with its family themes than any year-end Oscar baiting). Is it really as radical a departure as it seems. “Yeah, probably," Fincher says. "It doesn’t feel as radical to me in terms of some of the movies I’ve developed and tried to get off the ground, but I think for a lot of people it will be very different. Especially those people who associate me with being…”

Dark?

“Yeah.”