“It’s a bigger revolution than sound” — Martin Scorsese and Scott Z Burns on the rise of streaming

A version of this was originally published in The Scotsman in November 2019, less two months before the pandemic.

“A movie like The Report does not get made in Hollywood anymore,” says writer/director Scott Z Burns. The filmmaker is referring to his new based-on-fact dramatisation of Senate staffer Dan Jones’s monumental struggle to investigate the effectiveness of the CIA’s euphemistically named “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques” in the aftermath of 9/11.

Starring Adam Driver as Jones, the film dramatises his five-year odyssey to not only compile his damning report (which conclusively found no evidence that the CIA’s methods –including waterboarding – worked, thus rendering them illegal), but also the battle he then faced to get the information it contained released. “There was such a Kafka-esque journey that he had to go on just to get these 500 pages of redacted information out into the world,” says Burns. “Cinematically, that was one of the most interesting things about the story.”

It was also something that made it feel like a thematic throwback to the studio movies — Catch-22, Serpico, Network, All the President’s Men, The Front – that Burns grew up watching. Those were films that told important stories about people standing up to institutional authority. They’re also films that would never get made within the studio system today. Given the subject matter of The Report, it’s ironic that it has become so difficult to get a film like this out into a world that would actually benefit from what it has to say.

That we’re getting to see the film at all is testament to Burns’s determination to make it. But it’s also a testament to the disruption of the distribution system currently being brought about by tech giants such as Amazon, which will stream The Report two weeks after debuting it in cinemas, and Netflix, which has just released another of Burns’s projects, The Laundromat, a Meryl Streep-starring black comedy about the Panama Papers that he wrote for long-term collaborator Steven Soderbergh (Burns also wrote the scripts for Soderbergh’s The Informant!, Contagion and Side Effects).

Though both projects have starry casts, neither could be considered easy sells in the current cinematic climate. Studios are focused almost exclusively on franchise movies and it’s become harder and harder to get adult-oriented narrative films in front of audiences unless they possess some kind of obvious Oscar buzz that can justify the vast sums required to position and market them as such.

“The fact that Amazon is willing to put it on a streaming service so that it will reach people in corners of the world that it never would have with a theatrical release is important to me because I want them to have the experience,” confirms Burns. At the same time, he can’t help but be concerned about what this reliance on streaming will mean for the future of movie-going. “I think all of us who make movies want and hope for a big screen experience, if for no other reason than the very obvious thing of seeing an actor’s face being 20 feet tall allows you to look at emotion as if through a microscope and really, really, be transformed by it. When you become bigger than the image, when it’s on your phone, or on your TV, and you can pause it, you become the master of the pace of it and the size of it. That’s a different thing.”

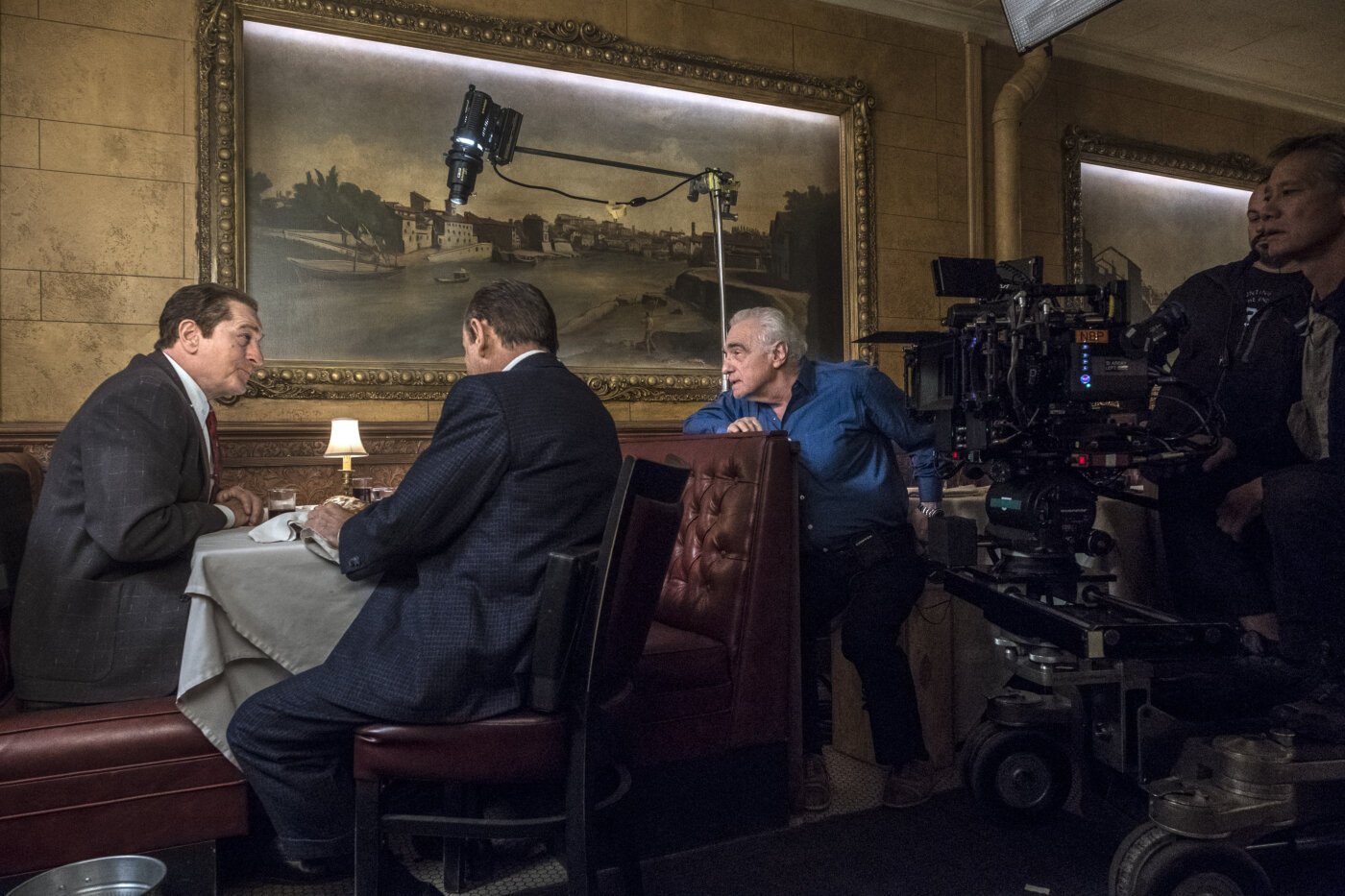

How different a thing? “It’s an even bigger revolution than sound was,” says Martin Scorsese. Holding court alongside Robert De Niro and Al Pacino ahead of the London Film Festival premiere of their new Netflix-financed gangster epic, The Irishman, America’s most celebrated filmmaker is under no illusions about the changes currently sweeping the industry. “It’s the revolution of cinema itself,” he says. “The original conception of what a film is and where it is to be seen has changed so radically.”

Scorsese’s film undoubtedly represents streaming’s biggest challenge to the slow-moving film industry. Scheduled to debut on Netflix within a month of its limited cinematic release, the film – a sweeping gangster drama about real-life mafia hitman Frank Sheeran (De Niro) and his suspected involvement in the disappearance of famed union boss Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino) — is a cinephile’s dream, re-teaming Scorsese with De Niro and marking the director’s first ever collaboration with Pacino. Nevertheless, the reality is that most people will watch it at home, on Netflix, not in a cinema.

Scorsese is sanguine about this. “There’s no doubt that seeing a film with an audience is really, really important,” he says, a wry smile creeping across his face. “There is a problem though in that you have to make the film.”

Yes, even with this cast and their shared cinematic history, Scorsese found himself facing the same problem as Burns: a reluctance within the Hollywood studio system to finance this kind of grown-up fare. Scorsese and De Niro spent more than a decade developing the film to no avail, so to have the deep-pocketed Netflix step in and tell them “you will have no interference; make the picture you want” was an offer they couldn’t refuse.

“The trade-off is that it streams – with theatrical distribution prior to that,” Scorsese says.

That’s similar to the deal Burns struck. Though he made The Report independently, when he sold distribution rights to Amazon at this year’s Sundance Film Festival he insisted on some form of cinematic release. To their credit, he says, there was never any pushback on this. Many cinema chains in the UK and US, however, are refusing to book Netflix or Amazon-backed films precisely because of their refusal to respect the traditional 90-day window between a film’s theatrical release and its home entertainment release.

But the willingness of cinema chains to become, as Scorsese puts it, “amusement parks” and screen only “Marvel-type films” – which he’s adamant are “not cinema” – is one of the reasons the tech giants have been able to disrupt the system. “The theatre owners need to step up,” insists Scorsese.

The upside for audiences is choice. Independent cinemas and film festivals like London (where The Report also premiered) are reaping the benefits of Netflix and Amazon backing more and more quality drama – and audiences with easy access to these can choose whether to have the communal experience of seeing a destined-for-streaming film on the big screen or in the comfort of their own home. What’s more, that choice is not mutually exclusive: cinemas can screen The Irishman even after it’s on Netflix.

Yet for the first time ever, film fans with limited opportunities to get to the movies can now be part of the cultural conversation at the same time as everyone else.

The big question is whether this best-of-both-worlds scenario will expand or contract and whether or not the way films are designed and shot will change if their prime destination is no longer an actual cinema screen.

“What streaming means and how that’s going to define a new form of cinema, I’m not sure,” says Scorsese. “What has to be protected is the singular experience.”

“I have this conversation a lot with friends of mine who are directors,” says Burns. “Like everything else that’s happened with technology, there’s an incredible upside. And there’s also a downside. If we’re losing part of an authentic experience for the sake of convenience, that’s a conversation that we really need to continue to have. There are no easy answers.”